I had the distinct pleasure of prototyping a new initiative aimed at cultivating a discipline of civic innovation at Yale College, led by Dean Holloway and alumnus Eric Liu and his brilliant organization, Citizen University. The program investigated some of the values, systems and skills required to participate in and lead a thriving culture of civic participation. Complementing my fellow speakers, including the founder of the Warrior-Scholar Project and the leader behind the country’s first Future Caucus, I focused on the art of framing problems as a critical skill in developing the civic imagination required for transformative societal impact.

Curious Catalyst founder, Kaz Brecher, sharing her passion for civic innovation with Yale College students.

I began by sharing the formative nature of my time at Stanford University, studying social psychology with Prof. Phil Zimbardo who was responsible for the now-infamous Prison Experiment. He and Yale professor, Stanley Milgram, were profoundly shaped by the questions that arose out of WWII – were certain people inherently evil or could circumstance illicit evil behavior from anyone? Their investigations around the role of authority figures and social constructs continue to reverberate today, in everything from the torture at Abu Ghraib to the very structures of how power is wielded and held across our communities. As the result of spending several classes with Zimbardo, most memorably Mind Control, I have developed a deep proclivity to question everything – authority as a matter of course but also myself.

Interest in Philip Zimbardo's work remains high as evidenced by the premiere of 'The Stanford Prison Experiment' at Sundance in which Billy Crudup embodies the mad professor

Why question myself? By way of explanation, I offer this portion of David Foster Wallace’s 2005 commencement speech, “This is Water,” for its profound simplicity:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says "Morning, boys. How's the water?" And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes "What the hell is water?"

Civic imagination requires this level of self-awareness and questioning – so that we might find new approaches to addressing the entrenched challenges plaguing out cities and nations. At Curious Catalyst, we define entrenched challenges as those receiving aid in one form or another for more than 10 years resulting in little to no impact. Food deserts, the complexity of which I previously covered here; homelessness and deinstitutionalized populations; waste management; pollution of our air and water. You get the picture.

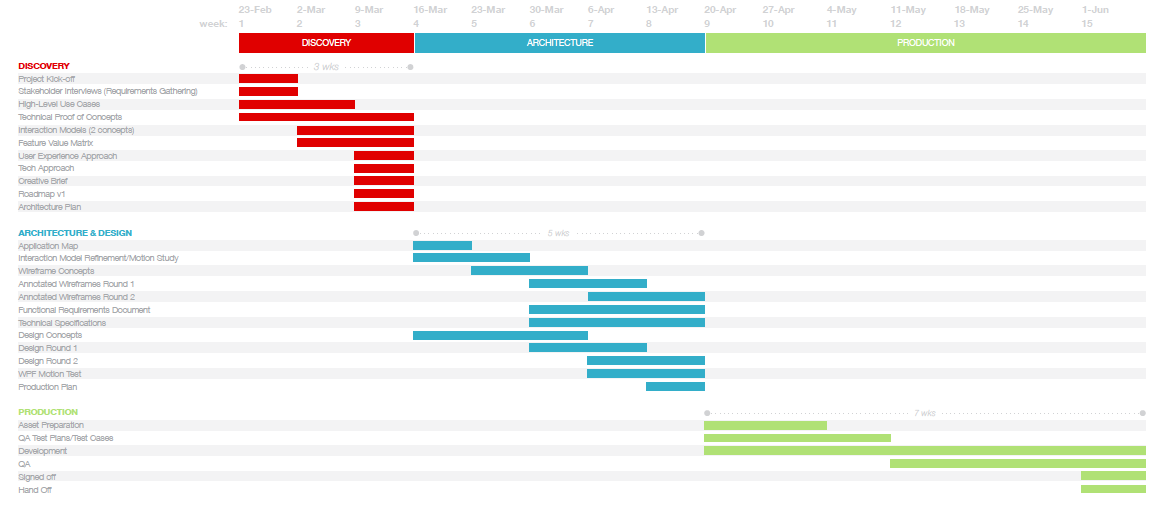

So, when asked to share some of the skills needed to embody civic leadership, I immediately knew I had to share a powerful technique for framing issues differently. A recovering McKinsey friend often says that we have too many people brilliantly solving the wrong problems. But how might we get through our folly and find the right problems to solve? As a member of the faculty at THNK School of Creative Leadership, I use a Reframe tool that was designed to counteract our powerful cognitive biases, exactly the type against which Zimbardo often warned. In four steps, we identify limiting core beliefs around a complex challenge, tease out beliefs that support that perspective, and then do some mental gymnastics to flip them around. This results in a reframed core belief which, when well executed, points towards a new solution space. A “structured approach to creativity” may seem impossible, but it’s worth trying for yourself with the online version here.

What do you see when you look at this image? Homelessness? Poverty? Addiction? Our new THNK campus in Vancouver is situated at the edge of what is known as the Downtown East Side (DTES), the poorest postal code in Canada and one in which almost 5000 drug users occupy the 10 square blocks. In 2007, nearly a third of the DTES inhabitants were estimated to be HIV-positive, a rate on par with Botswana’s. Twice that number had hepatitis C. Dozens die of drug overdoses every year. And I have been deeply moved by a movement known as Harm Reduction, a fundamental shift that acknowledges that people WILL get high, and taxpayers will foot the bill for mitigation somewhere along the line (think ER visits vs. clean needles).

The visionaries and pioneers behind this shift demonstrated exactly the kind of civic imagination to which I believe we all must aspire. When they looked at this neighborhood, they saw the drug users within the ecosystem of a public health crisis not as the source of a criminal epidemic. By reframing dealers as part of a solution, they were able to mount an incredibly successful effort to get needles cleaned up and users into environments where medical attention could support safer practices. Since Vancouver began seriously supporting needle exchanges and other such tactics, HIV infections have fallen by half, and hepatitis C rates have plunged by two-thirds, according to city and provincial health authorities.

UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon recently shared his vision for after the millennium development goals expire this year. At the heart of a new report, and in its title, is the word “dignity.” His framing begs the question, “what might our cities and communities look like if we solved for dignity instead of poverty?” And how might we be complicit in a destructive paucity of civic imagination when boiling down solutions for problems like obesity in food deserts to the need for more supermarkets, for example? The brighter future we envision requires a richness and rigor applied to how we frame our understanding of the world.

What are YOU doing to bring a new perspective to your work? If we heed Zimbardo, even asking the question is a good start.